With the cricket season upon us, Chris Kumeroa, Managing Director of Global Risk Consulting, draws from years of security experience in Pakistan and the Middle East to risk assess the potential for an NZ Cricket return to Pakistan.

When I read back in 2018 that the New Zealand Cricket Council was to carry out “due diligence” as they considered a request from Pakistan to play a Twenty20 game in Lahore, my first reaction was that Pakistan posed significant travel and security challenges.

A number of highly experienced security risk management consulting companies have had personnel who have operated in this region for a number of years and seen first-hand the dangers when trying to operate within this environment.

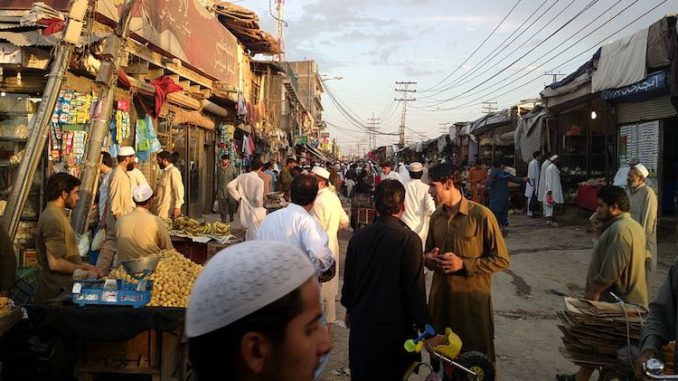

Pakistan is considered one of the most dangerous countries in the world (11th least peaceful in the 2019 Global Peace Index). In 2009, international sporting tours were stopped after gunmen killed five people on the Sri Lankan team bus. New Zealand Cricket hasn’t played in Pakistan since 2003 because of security concerns, with the UAE becoming home base for the Pakistan team.

The internal security issues that plague Pakistan are greatly influenced by its neighbours, Iran, Afghanistan, India and Kashmir, and other geopolitical factors.

The Pakistan Context

Pakistan has two major allies, both superpowers and economic partners to Pakistan: China and the US. The Americans have invested heavily in Pakistan in recent decades, providing financial support for securing north-western borders and combating terrorism in FATA/Swat, KPK and Baluchistan. For a number of years, the government had been slightly reluctant to intervene in FATA, KPK and Baluchistan’s (all rated extreme risk) political and security affairs with any form of military presence, although this has since changed.

A guerrilla war waged by Baloch nationalists had kept the region – that borders Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan – unstable and in turmoil for decades. The strong Taliban presence in the tribal areas of KPK has also made that province extremely difficult for the government to manage.

Political instability continues to plague Pakistan. There have been a number of military coups since the nation gained independence from Britain over seventy years ago. The absence of a strong political system and allegations of corruption over many years have given rise to crime and armed conflict, which has increased with international terror groups such as al Qaeda, the Taliban and ISIS (Daesh) more recently.

It had been planned that a Silk Road corridor to be established by the Chinese; a six-lane highway from the northern China border to the Gwada port, in southern Baluchistan. The Silk Road would give China direct and easy access to Middle Eastern and African markets.

Chinese investment into Pakistan will be substantial and would allow Pakistan to modernise and potentially unlock its rich natural resources, including oil and gas, gold and coal.

At the time, Pakistan’s government wanted to bring stability to the region to ensure the Silk Road proceeded, and conducted a sustained military offensive against domestic militants in the west of the country. A number of Taliban commanders were captured or killed by the Pakistan Military, and others will killed by US drone strikes in cross-border operations.

The risk assessment identifying security concerns facing the development of the Silk Road are the same issues that face tourists, businesses wishing to establish a base for commercial activity, and international cricket teams considering touring the country.

Enjoying this article? Consider a subscription to the print edition of New Zealand Security Magazine.

Assessing Security Risks

I spent two years in Pakistan as Country Security Risk Manager for one of the world’s largest oil and gas service providers, based in Islamabad. It was a dynamic and complex environment, characterised by security risk levels that constantly shifted as a result of political decisions and security incidents. This would invariably affect the “Country Alert State” and, consequentially, our security advice.

Pakistan risk levels are assessed as High (-12.2 out of -25) on the basis of a Country Security Risk Assessment System in which quantitative and qualitative data is crossed referenced by senior analysts and experienced global security consultants to ensure the threat and risk levels match trends on the ground.

It is important to measure all security elements (including political, terrorism, travel, operational and security risks) within the threat landscape so as to adjust the ratings accordingly.

If no adjustments are made as a result of misinterpretation of risks this gives rise to vulnerabilities for an organisation as extremists and criminal elements become adept at spotting weaknesses within a security structure. These can invariably lead to fatalities, injuries and a loss of business at the hands of sophisticated, well-funded, well-organised and sometimes complex attacks.

When trying to improve security outcomes, it’s important to meet with the citizens and law enforcement of local communities. If you apply a hearts and mind approach they are a great source of free information, effectively becoming allies to your broader security cause.

More often than not this is a usual first step for current and former Special Forces personnel and the Private Security world, but for individuals and companies operating on their own, getting the locals on side is an often overlooked practice leading to unfortunate consequences.

Getting the lay of the land early and trusting your instincts about the environment and people you deal with (what feels right and comfortable – developing and trusting your sixth sense) is important. Occasionally this means engaging a local (preferably former military or law enforcement officer – referred to you by the state) that understands the environment and is able to interpret it in a way that promotes safe operations.

Local support

Once you have established the country and area risk levels and ratings, the next step, as it should be in the case of a New Zealand Cricket Team tour, is to establish what additional support is required by the host nation and private security providers to achieve acceptable levels of control that match or exceed the organisational threshold and are line with a security management plan. This is known as the risk-based approach.

Not long ago I stood in an underground bunker, under a safe house controlled by the US military, and listened to the mission breakdown of the hunt for Bin Laden. The US conducted it without Pakistan’s consent or knowledge.

This placed significant political pressure on an already frail relationship in which they needed each other to combat the growing influence of the Taliban and ISIS in the region, who were using Pakistan as a base to launch attacks against Coalition forces in Afghanistan.

The attack on Bin Laden led to ongoing suspicion by the ISI (Pakistan Secrete Intelligence Service) that other foreign nations had intelligence personnel operating within its borders. It would be fair to say that all foreigners are now treated with suspicion, which presents new challenges for any security risk management provider.

Anyone venturing into Pakistan, such as sporting teams or businesspeople, should bear this in mind. Reliance on government cooperation, whilst seemingly enthusiastically given, might not always be as reliable as an independent body familiar with the local environment.

If a cricket match were to go ahead, this should be based on a comprehensive threat and risk assessment of the current political state of Pakistan and past and current shifts in the security operating environment. After establishing minimum security standards, state support for pre-match visits and for the tour itself should be requested.

In conclusion

A cricket match would be hugely significant for the game internationally and for the country as whole, but it will come with its inherent challenges on the security front, particularly if extremists were to see it as an opportunity to demonstrate to the West (not just New Zealand) that they can still create havoc.

The Taliban have long memories and understand New Zealand’s role with the Coalition in Afghanistan some years ago, and they could use this as an opportunity for payback if a soft target presented itself.

We have a saying in security: we as security providers have to be lucky all the time, whereas terrorists or highly sophisticated criminal groups only have to be lucky once.