Covid-19 has set the scene for vehement public displays of non-confidence in governments around the Western world, writes Dr John Battersby. Are democracies of the West about to face their own ‘people’s spring?’

Over the last months Covid-19 has completely dominated the world’s media, and it is just possible that many terrorists will be watching in awe at the devastation, disruption and sheer power to compel comprehensive change that has been brought about by a tiny virus.

The power to absolutely dislocate the status quo and create conditions for a ‘new normal’ is precisely what terrorists seeking to bring about change by violence have been attempting for as long as authority systems have existed. Most of the time the terrorists were doomed to fail, or were compelled to accept negotiated outcomes representing little improvement on where they started from. On the occasions when terrorists did succeed, they never created change on a scale like this.

Then, to add to the apparent impotence of terrorism, the bungled arrest of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police Officers has led to mass protests in the United States, United Kingdom and Europe, some of them devolving into violence and looting.

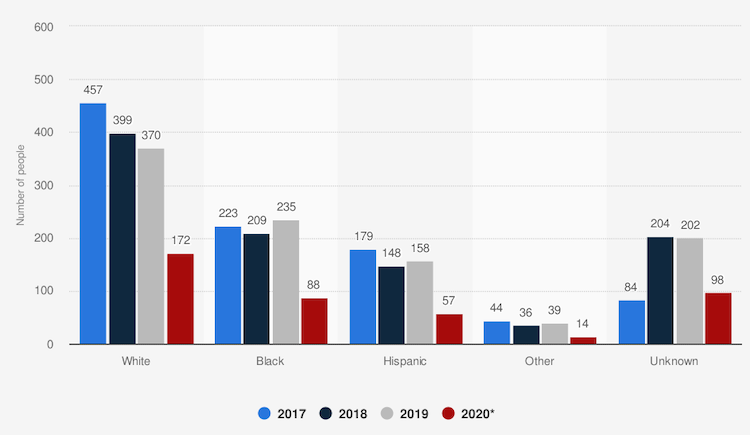

The force used in the George Floyd arrest was horrifyingly unnecessary, with a predictably tragic outcome. But it was not the singularly unusual event that the world-wide reaction suggests it was.

The US homicide rate is five per 100,000 (or 15,498 in 2018) – significantly higher than the rate for Western Europe of one per 100,000. Annually, around 1,000 people are shot and killed by US police (this does not include deaths in custody or by means other than a firearm) – and an average of just over 100 police officers themselves die in the line of duty each year, over half by homicide.

In 2017, almost 40,000 Americans died by firearms (accident, suicide or homicide). Then to add to what appears to be a general ‘worthlessness’ of American life, in barely six months, 116,000 Americans have died of Covid-19 – a staggering rate, and roughly parallel to American losses in World War One.

The death of George Floyd was likely the flashpoint of built up frustrations about systemic carelessness and inequalities that have been rubbed raw by the Covid-19 death rate, the various lock-downs, increasing joblessness, and – critically – US medical and mental health systems which appear inadequate in times of normality, have been found desperately wanting amid the Covid-19 crisis.

This exposed vulnerability created a widespread feeling of insecurity. Insecurity has a tendency to drive people to extremes – and clearly it has. Then added to all this is the racialisation of the protest – curiously many forms of prejudice and inequality exist in our societies, but none seem to be able to ignite emotional reactions quite like racism does.

The US already has a tortured recent history on this head, which included extremes of Black and White Leftist terrorism in the 1970s – and emerging White Rightist terrorism in more recent times.

It is not just in the US that these circumstances have occurred, almost everywhere, every government – including our own – was caught unprepared, and not uncommonly it has been everyday people who have suffered the most.

Enjoying this article? Subscribe to updates by emailing ‘subscribe’ to editor@defsec.net.nz

A few seconds of social media footage of a police officer kneeling on a prone man’s neck proved the straw that broke the camel’s back. The question it begs – at a time when the welfare of people should be paramount – is: why is state force apparently being so carelessly and vividly portrayed oppressing them? There, in that snapshot, was the goal terrorists almost always seek to achieve – a visible display of the state being unable to protect its citizens.

The protests we are seeing each night on the television news are vastly more peaceful than are generally being reported, because the visual media (and their audiences – us) seem to feed on the entertainment of violence. But the protests most importantly are a challenge to authority, not just to the lawfulness of the use of force by police – but a statement to the leadership of states that they may have exceeded the social licence democratic systems allow their governments to have.

Whatever else they may have been doing, when people are in desperate need, they expect governments to deliver a better deal than most have. ‘We are all in this together’ – so the catch-cry goes, but actually we’re not, and that’s the problem.

Perhaps it is drawing too long a bow for direct comparison, but there are parallels here with recent history. On 17 December 2010, Tarek el-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor, died by setting himself on fire in protest against harassment from municipal officials. It was an individual, though not entirely isolated, tragedy that would likely have passed largely unnoticed but for the ability of social media to rapidly disseminate tiny grabs of footage that quickly incited emotional reactions – and ultimately it ignited the ‘Arab Spring’.

The self-immolation catalysed deep undercurrents of dissatisfaction about the behaviour of autocratic governments, the excessive use of state force, unemployment, corruption, and the lack of human and political rights, and prompted widespread protests across the Arab World. A number of regimes toppled as a result and the promise of better and brighter things for ordinary people prevailed for a short while.

But the popular movements, highly effective in some cases in removing despots from power, proved much less capable of constructing better alternatives. The chaos that followed in the 2010s allowed ISIS to germinate into a major regional and global threat and reduced Syria to years of devastating civil war. Following a long tradition of liberation movements generally failing to liberate anyone, the Arab Spring soon devolved to the much longer ‘Arab Winter’.

The question to be faced now is: is the West now about to face its own ‘people’s spring?’ The challenge for governments is to win back the respect of their populations, deeply bruised by Covid-19, by proving they do put the welfare of their citizens first, that human rights do matter, and that they can prepare for crises in such a way to minimise their impact on the rest of us. They need to do this quickly, before the protests continue, before more statues come down and before fault-lines within societies are aggravated.

Critically, the longer police are visually depicted in open confrontations with the populations they are sworn to protect, the more likely agenda-oriented interest groups will co-opt the chaotic space and take us to places we will ultimately regret going.

A hundred years ago, anarchist terrorists sought to overhaul authority per se. Osama bin Laden fantasised that his 9/11 attack on the World Trade Centre in New York would cause a global uprising and ISIS sought the dissolution of borders across the globe. All of their efforts, resources and influence were ineffectual breezes compared to the all-encompassing storm Covid-19 has brought about.

But terrorist inability to start the momentum of dis-stabilisation did not stop them exploiting the results of it for own ends, and far from alleviating the misery of ordinary people, they generally compounded it.

There is a tendency to regard terrorism as the presence of an existential threat, and that counter terrorism involves the disruption or apprehension of those presenting it. However, it is not confined to this, indeed broader assessments of possible environments in which threats might germinate is essential.

The respect and prestige of state institutions have been dealt a blow by the culmination of recent events, and this has to be recognised as a major problem to be rectified as quickly as possible with genuine solutions before the People’s Spring becomes the People’s Winter.